#55: Brussels' canalwijk wijkt

A photo essay and accompanying text on Brussels' canal district and what its ongoing metamorphosis means for the rest of the city and its future.

I’m writer Eoghan Walsh and this is my Brussels Notes newsletter (you can subscribe here). This week we’re talking Brussels’ canal neighbourhood, and its ongoing metamorphosis - with pictures!

I thought I had a killer intro for today’s newsletter. It involved me sitting down with a fresh pint of Zenne Pils on the terrace at Brasserie de la Senne, looking out over the Tour & Taxis complex. I’d pull out my notebook from my bag, click my pen, and look out over the old train sheds to gaze thoughtfully at the tops of the blue and red cranes hanging across the skyline behind them. And then I’d write insightfully about how the neighbourhoods down by the Brussels canal are changing.

Only, when I got down there on a bright blue Saturday morning, when I took my sweating glass of beer, and when I pulled out my notebook, I couldn’t see the cranes. The neighbourhood had already moved too quickly for me, and in the way was the big black lump of a building my kids call the Brooddoos (“lunchbox”). This is how it goes in the canalwijk, I’m never quite sure where things are, how long they’ve been there, and whether they’re still going to be there the next time I pass by. The Brooddoos has been around for a while, so I probably should have known my sightlines wouldn’t have worked.1 But, walking around later with my camera, I was surprised by other sights in the streetscape.

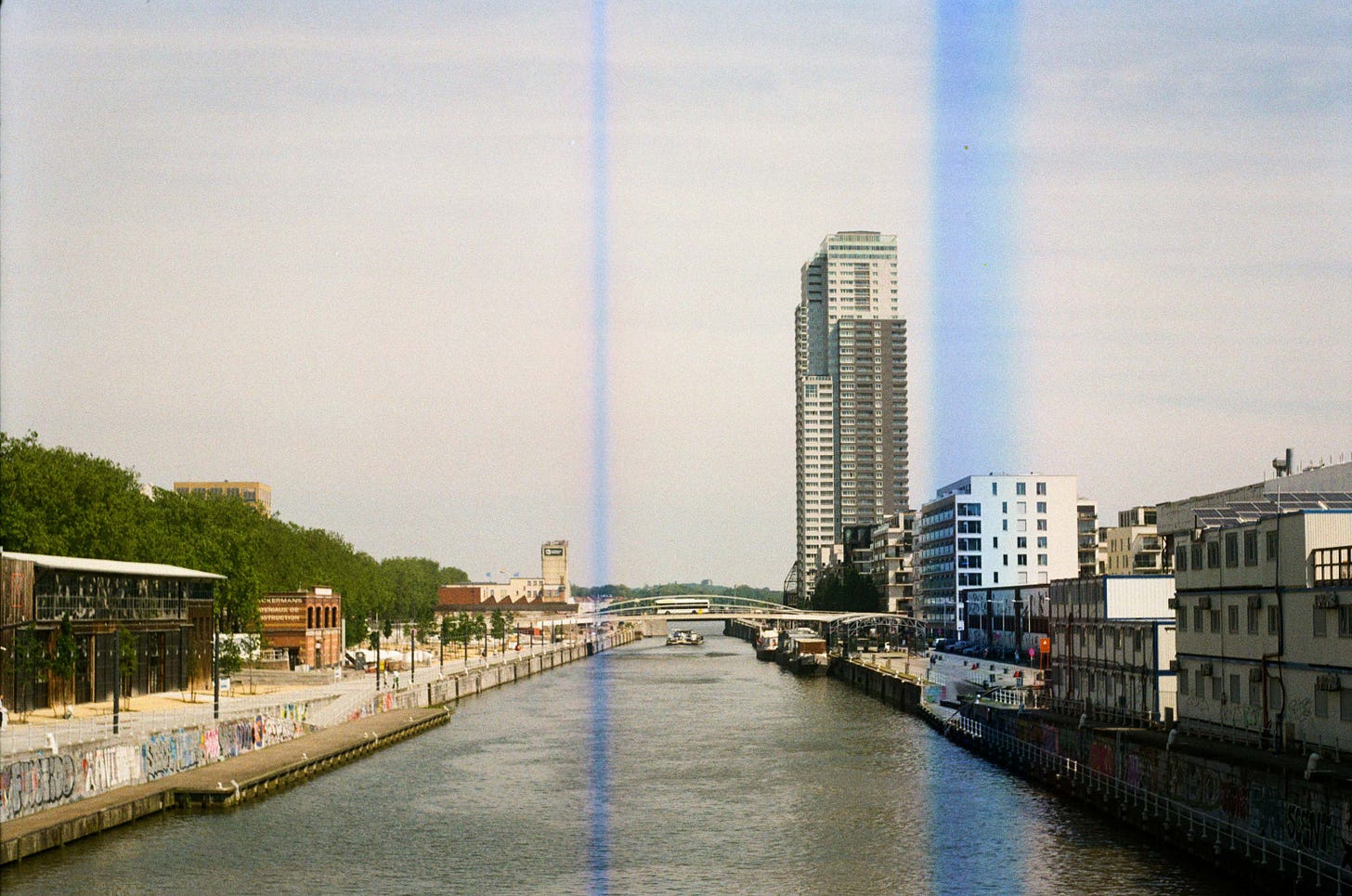

The former KBC office on the Havenlaan, the ugly post-modern office block? Now it’s just a big dusty hole in the ground, the building reduced to a tangled clump of warped steel and concrete. The graffitied warehouses opposite the entrance to Tour & Taxis that used to house the Magasin 4 concert venue and the Toestand non-profit organisation? Obliterated in anticipation of a new linear park running along the canal bank between Place des Armateurs and the new Suzan Daniel bridge. This is happening right the way down the canal, from Square de Trooz in Laken to the north to the Biestebroekdok in Anderlecht to the city’s southern edge, with empty lots and old buildings making way for new apartment complexes, pocket parks, and the occasional industrial space.

The canal, and the neighbourhoods that flank its banks, has always been both conduit for, and crucible of, urban change in Brussels - ever since it superseded the Zenne river several centuries ago as the city’s primary artery to the outside world. The river was always too haphazard, too uncontrollable to properly define the city, a spider pattern in a shattered piece of glass compared to the canal’s unswervingly straight lines. The canal connected Brussels with North Sea shipping at Antwerp and coal and steel country in Charleroi. It’s where the brewers and the tanners, the ironmongers and the carmakers settled, where the city connected itself to the country’s emerging railway network, and where Belgium’s industrial revolution properly took root.

It’s where poor Flemish farm labourers from Flanders moved to work in their factories, later to be succeeded by arrivals from Italy, Spain, and the Maghreb. When the factories closed or relocated out of the city in the 1970s and 1980s, the canalside neighbourhoods bore the brunt of the social dislocation and many of them continue to bear witness to that calamity as the so-called arme sikkel of districts that cut through Brussels in a sort of a half-moon arc of entrenched poverty.

In more recent years, the canal neighbourhoods have experienced radicalisation, gentrification, and the compound challenges of twin housing and drug crises. The water remains a powerful psychogeographical barrier between two distinct versions of cosmopolitan Brussels - Rue Antoine Dansaert and its Dansaertvlamingen yuppies on one side and a centre of working class, North African Brussels on the Gentsestweenweg opposite. In the recently-built loft developments on the Quai des Charbonnages and on the computer-rendered adverts for not-yet-built compounds further along the Havenlaan, you can see the encroachment of the former into the latter’s territory, as the city’s urban planners undertake an experiment to test two potential futures for this part of town, for for Brussels more generally - as a Productive City, and as a Liveable City.

Brasserie de la Senne represents the former impulse, as do the cement factory and construction material wholesalers opposite it, a gamble by Brussels officials that they can create space in the city for medium and light industry, lure businesses to occupy them, keep these kinds of jobs within the city limits, and provide meaningful work for the people who live nearby. All while adding more housing to the mix.

But these are subtle changes to an area of Brussels that never quite sloughed off its industrial patina. More obvious are the recent interventions to make the canalwijk more hospitable for its residents, to make it a city “on a human scale” as the wonks might say. The Tour & Taxis park is the most visible, and successful, of these changes. The broken-down old warehouses opposite have been demolished to make way for a skatepark, football cages, and grass lawns. Across the water, the Kaaitheater is undergoing substantial renovations and the former Citroen garage has been gutted in anticipation of the multidisciplinary arts centre that’s going to occupy it in a couple of years, of which the Kanal Pompidou museum is the most high-profile tenant. Elsewhere there are works at all the major bridges crossing the canal to install pedestrian walkways, bike lanes, and whatever green spaces urban planners can eke out between the road and the water.

It’s a stop-start affair, to be sure, and many people who live on the canal’s edge would say it’s not going fast or far enough. Others might say it’s going too far, that these interventions are little more than cosmetic changes intended to attract the middle classes to the detriment of existing residents, and that they don’t address the more immediate socio-economic and public safety problems of the area.

It’s nice to have new parks - in one of the densest, greyest parts of Brussels - but them coming at the expense of more anarchic spaces like Magasin 42 means Brussels loses some of its spontaneity even as it gets a little bit greener. Whether or not these twin visions - of a productive, people-centred city - succeed in embedding themselves into a future Brussels is not something I can judge from my little walk around the neighbourhood with a couple of beers onboard. But, as it has always been throughout its history, the canalwijk remains a laboratory for testing out the ideas of what kind of a city Brussels can, or wants to, be.

And anyway, every knows the best view of the canal neigh

bourhood is from the Jubelfeest bridge in the T&T park.

Never fear, they just broke ground on a purpose-built site between Brasserie de la Senne and BeHere.

Over the last couple,of years, I’ve been biting off small pieces of the canal each time I’ve been in Belgium. So far, I’ve extended to Tubize, south of Brussels and to Kanaalbrug Tisselt (around Duval Brewery) to the north. I just sent my university students back to Boston, and so hope to add a few more kilometers of canal walking before I have to return to America at the start of August.