I’m writer Eoghan Walsh and this is my weekly free-to-subscribe newsletter about life in Brussels. If you like it and you’re not already subscribed, you can sign up here!

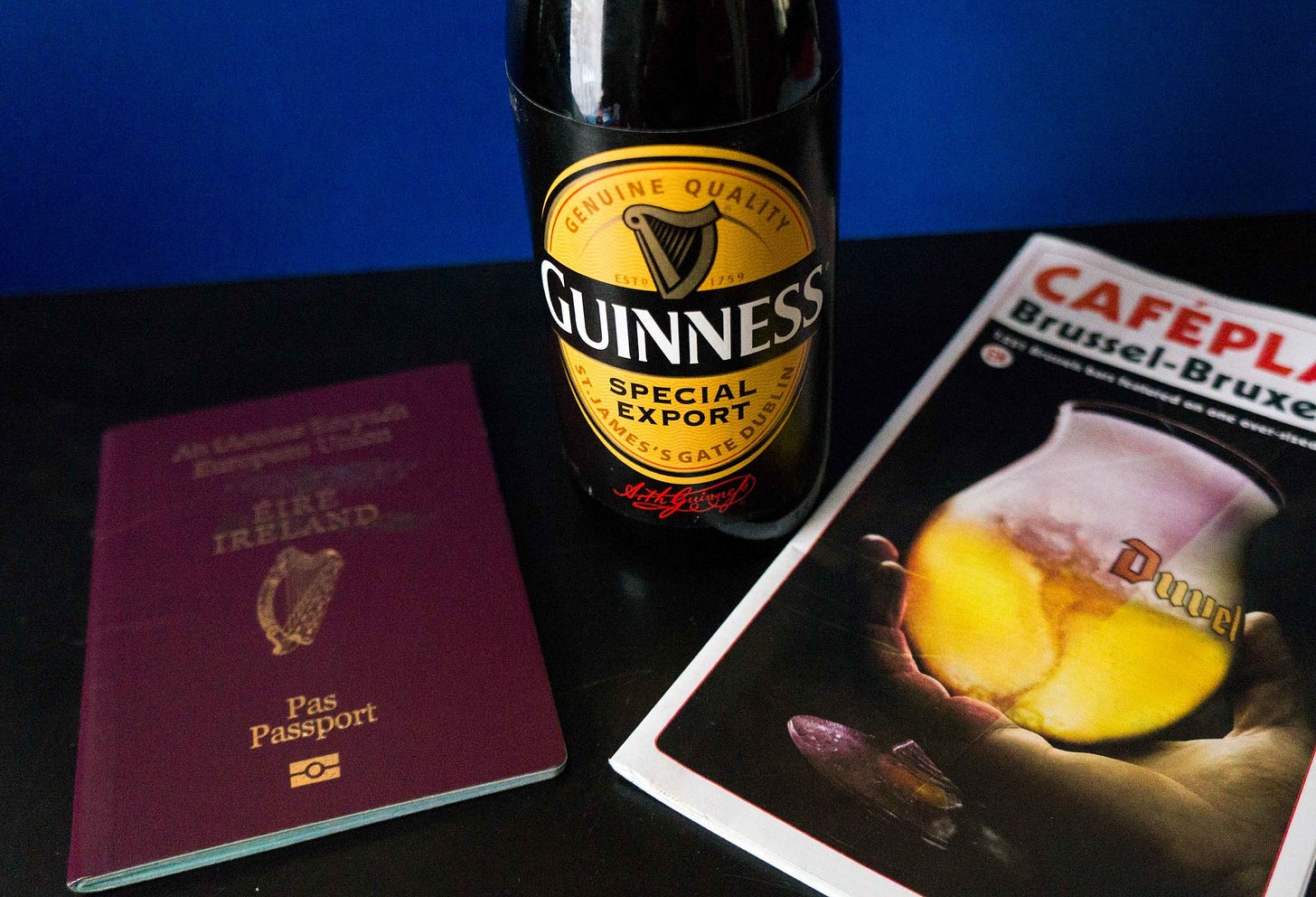

This week’s newsletter is going easy on itself. Spring is here but has not yet sprung, and a trip back to Dublin this weekend made me think how the city of my birth city and my adoptive city at not all that different. Read on…

The weekend just gone I was back in Ireland, for the wedding of an old school friend in Dublin’s city hall. Though I was born there, lived the first two years of my life on the north side (yup Cabra), and still have family there, it’s not a city I know particularly well. As I've written previously for this newsletter, I’ve never really felt like I fit there. I’ve never lived there as an adult, and any childhood visits were usually restricted to the suburbs (yup Dublin 6W). But with four trips back in the past 12 months - which must be a record, for me - I’ve come to know it better, helped along by long walks tramping around town listening to Donal Fallon’s excellent Three Castles Burning podcast on my way to and from the pub. Just as I will in all likelihood never quite qualify as Bruxellois, I will never be a Dub - my accent will always betray me - but I’m getting a better grasp on the town my mother grew up in and which, in an alternate reality where we never moved to Cork, might have grown up in too.

I’ve experienced Dublin’s ups and downs over the past two decades second-hand, through stories of friends who’ve moved back there from Brussels and struggled to find somewhere to settle down, or friends who’ve moved here from there and are visibly relieved to be living in a city with functioning health and public transport systems.

On Friday night, I loitered outside the wedding reception venue on Dawson St with another school friend so I could keep him company while he vaped and he could keep me company while I got some fresh air. As I was standing there watching him puff giant plumes of fruity vapor into the sky, he gave a quiet nod in the direction of a young man in tracksuit pants lurking on the other side of the velvet rope. “Situational awareness. That’s what you need to have,” he said from one side of his mouth.

R is a police officer, and when we were younger was always keen to instill in me the importance of his street smarts relative to my book smarts. And so we fell into talking, as men creeping towards middle age do, about what things were like when we were young and virile, and how things were going to the dogs lately, just as we were starting to creak and fray around the edges. The gurriers and the pickpockets and the scammers were more brazen these days, we agreed. We also concurred on the general decline in urban civility since the pandemic - people listening to music without headphones on the bus, littering, petty inconveniences - though we couldn’t put our fingers exactly on the source or cause.

And as we flipped through the ills of contemporary society, I was struck by how much overlap there was between what Brussels has been going through, and the challenges Dublin has faced in recent years. Now, the cities are very different. An unexpected example of this came the following night, when all the wedding guests had gone back down country and L and I were left to our own devices for a night in the city without children. I am not, nor have I ever been, a great Irish Pint Man, which explains my somewhat foolish notion that we could stroll into a city centre pub in Dublin on an early Saturday evening during Six Nations seasons and secure a couple of chairs and a table, where we could sit and have a quiet pint and read a book.

There was no joy at Slattery’s or McNeill’s on Capet St, and across Grattan Bridge we hadn’t any more luck, with McDaid’s, The Banker’s, Grogans, and The Hairy Lemon all jammed. We skipped even trying Bruxelles because it was too raucous (and too on the nose - but with the opening of The Dubliner in Brussels in 2024, it is interesting that both cities now have pubs named after each other). We managed to get half a stool and a quarter of a pint before abandoning the Palace, and it was only once we’d managed to wedge ourselves into the big snug at Neary’s that L turned to me and said, “It’s so strange, this standing up in bars. We really don’t have that tradition at all back home.” It had never really struck me, but she was right; Brussels pubs are lively, for sure, but in a more relaxed, less manic kind of a way. Maybe it’s because the pubs here in Brussels never really close that there isn’t the impulsive rush to get in early and stay as long as you can. Maybe it has to do with the prevalence of table service, meaning you don’t end up with drinkers naturally clumping together at the bar waiting to be served. But on an equivalent early Saturday evening in Brussels, you wouldn’t find people standing three deep in the middle of a pub, and if you did you’d just go around the corner to the next place and probably be able to find a seat and a quiet corner.

There are other, more obvious differences between the two cities. Dublin (depending on how you define it) is, for one, three times as large as Brussels, but is home to almost the same number of people - leading to a much more diffuse, suburban city. Both may be capitals, but Dublin was never an imperial capital, and Brussels does not have the hang-ups attendant to a former imperial outpost. Brussels has 19 elected mayors and one minister-president, while Dublin continues to be run by an unelected chief executive. Then there are the more quotidian divergences - Dublin’s monolingualism versus Brussels’ dual language communities, the absence of a metro in the former, and both a coastline and a river in the latter.

But R and I were able to bond over the state of the world because there was so much overlap between the two. In the sense that everyday incivility is on the rise, revealing itself in Dublin and Brussels in things like those teenagers listening to music on speaker or pensioners facetime their children without headphones, dirtier streets, and a sense that petty crime is both on the rise and going unchallenged. Dereliction is a blight on both, with whole streets in Brussels’ hypercentre given over to buildings on the edge of collapse, and Dublin looking dead from the waist upo because they can’t seem to work out how to install apartments over shops. Both cities are suffering under the same epidemic of cheap crack cocaine among their precarious populations, exacerbating underlying social issues, the both same dug-in opposition to supervised drug use centres and more progressive drug policies.

They share rampant homelessness crises, and similar struggles to cope with the challenge of housing refugees and people seeking international protection. They have the same mobility challenges, and the same problems weaning themselves off their 20th century car-centric attitude to city planning. Measured in GDP, on paper the two cities are grotesquely wealthy but also home to communities living in poverty and significant, generational deprivation. Housing markets running so hot they’re shutting out all but the deepest pockets from taking advantage of city life - though in this, even Brussels can’t compete with Dublin’s bonkers housing and rental market.

It feels as if both cities are also grappling with identity crises. Listening to Donal’s podcast, and the stories he tells of the city’s history and its characters, what comes through so clearly is Dublin’s self of itself, what kind of city it was and saw itself as. The capital of a young republic, a literary capital, the cultural centre of the country, a port city, a rebellious city. But lately it feels as if all that is being undermined by the fatal Irish disease of the need for external validation, the lure of international techno-capitalism infiltrating the city with other people’s money, eradicating the charm and the character that made Dublin Dublin, and erecting in its place indifferent, anonymous architecture, and hotels. So many hotels.

If Dublin is scrabbling around to keep what’s left of the city it used to be, Brussels seems still to be a city without a precise idea of what it is at all. Industrialisation came late to Brussels, and left early. The city never really wore the mantle of imperial metropolis very comfortably, and now seems stuck somewhere between the provincial northern European capital it was - and its 19 municipal councils still treat it as - and the self-described “capital of Europe” it’s trying to be. 36 years after its creation, it’s still unclear what the identity of the Brussels region really is, except in opposition to what it’s not (Flemish or Wallonian, and some bad faith actors would say hardly Belgian either). It wants to be a modern, innovative city, but too often reaches back into the past for solutions to deal with today’s problems. It wants to bring back industry to the city, but keeps building houses in the city’s old industrial quarters. The 20th century killed the old Brussels, a city where Bruxellois could trace their roots back through generations. 21st century Brussels is a city where everyone comes from somewhere else, and no one has quite worked out what that means. “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Or something.

Politicians say they want to stop the middle-class from fleeing, but do nothing to make the city more liveable. There is no coherent vision of where the city should be in five, 10, 15 years - and how could there be when there’s 19 mayors pushing 19 different perspectives and a regional government above them trying and failing to nudge them in the same direction. It’s a city-state that’s been run by socialists since its creation which just elected its most right-leaning parliament in recent memory. De jure bilingual but de facto multilingual and ignorant, if not contemptuous, of its Dutch-speaking heritage.

The terrorist attacks and manhunts of the 2010s, the pandemic, and the cost of living crisis seem to have knocked the city’s belief in itself, and the results are all around us. If I think back to 2019 and how the city was then, I would have been much more confident in saying, “This is what Brussels is about.” not that the city didn’t have its problems then - much of what we’re dealing with was around six years ago, but it’s just gotten worse and become more visible in the years since. It’s just that, then, it looked as if the city had righted itself after the trauma of 2016 and had a clear vision of how it was going to tackle the coming decade - a progressive city, primed to deal with the climate crisis, housing, and modernizing the city economy.

Now, I’ve been berated in recent weeks for what some people have described as the negative or pessimistic tone of recent newsletters. Concerned colleagues have even asked if I’m “doing okay”. And reading the above you might think that I am not, and that this is another scream into the void. But it’s not. Leaving R to his vapes on Friday night, I took comfort in the fact that, though we like to think the city we live in to be uniquely awful, that its faults are uniquely Brussels or Dublin, that they reveal some intrinsic failure in our hometowns - they are not. Brussels and Dublin for all their differences are facing - to a greater or lesser degree - the same challenges. And I'm sure people reading this in cities other than these two will recognise some or all of what I’ve written as applying to their towns too. We are, after all, living through an unprecedented, continent-wide housing crisis in Europe, and drugs have never been cheaper or more widely available.

Politicians like to argue that the problems of their city are sui generis, that what worked there won’t work here, “Because Brussels is different.” But this is just nebulous cultural exceptionalism covering for parochial defensiveness, elite self-preservation. If problems are unique to here, so it goes, then politicians from here are uniquely capable of resolving them, international best practice be damned.

There is some comfort, and maybe we can find some solidarity, in the idea, to mangle Tolstoy, that all happy cities might be happy in different ways, but all unhappy cities are unhappy in the same ways.

Re the pubs thing, I'm guessing the licensing system in Brussels allows pubs to exist in the sizes and locations that the drinkers want them. In Dublin they exist where they were in 1902, minus the ones where the licences were sold off to become supermarkets. The owners of those bars where customers stand three-deep are the same people campaigning for VAT reduction and berating their suppliers for price gouging because their industry is allegedly on its knees. Like with the housing problem, the pub industry has been shaped by powerful vested interests with the ear of a succession of right-wing governments. Frequently, the landlords, publicans and politicians are literally the same people.

Another great piece Eoghan, well done. I think the problems in both cities boil back to inequality (again and always). I used to think that Brussels has a better safety net and still do but it seems to be fraying. Having many workers living and paying their taxes outside the Brussels region does not help either. Bring on the congestion charge I say! Otherwise I still love living in Brussels but a river and a coast line would be nice (the canal is coming along well though!).