I’m writer Eoghan Walsh and this is my weekly free-to-subscribe Brussels Notes newsletter. If you’re not already aware, the pope was in Brussels the weekend just passed, and he came to our local church. There was a big hullaballoo. (P.S. this is coming a day later because I was visited by two migraines this week - one bad, one tolerable.)

If you like it and you’re not already subscribed, you can sign up here!

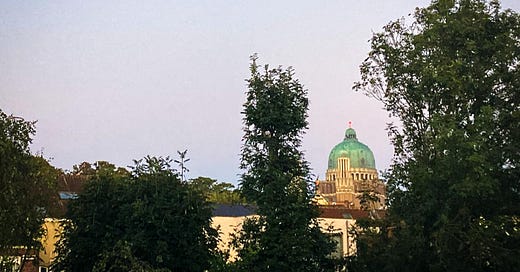

“Il vient quand, le pape?” the man in the powder blue overalls asked me. We were standing together on the narrow footpath outside our local bakery, squeezed between the bakery’s closed front door and the metal fencing separating us from the entrance to Koekelberg’s basilica across the street.

The pope’s visit on the last Saturday morning in September amounted to big news in our corner of Brussels, as much for the feared traffic chaos it would bring in its wake as any papal mania it prompted in the neighbours. Many of the people making up the thin reed of a crowd manning this temporary papal cordon either side of me looked as if they’d only just rolled out of bed and were still processing their morning coffee, here more out of morbid curiosity than any kind of personal religiosity. That was for the people on the other side of the fence, the ones lining the interior perimeter on the grounds of the church, who’d signed up months in advance for a spot and who’d gotten up and onto buses with names like “Toussaint” emblazoned on them at six in the morning to make it to Brussels in time. We were not those people.

In fact, passing by the same spot an hour earlier, I’d seen even fewer lingerers. A gaggle of uniformed police talked quietly into their radios while opposite them outside Le Grand Duc a pair of stringy youths in black tracksuits and hoods up pulled on cigarettes and took in the circus. A trio of African women passed the café terrace, anxious not to be late but looking lost. An elderly woman grasped the mass booklet in one hand and her adult daugther’s in the other. She in turn used her free hand to manoeuvre a buggy with a small child in it so that all three of them stayed on the slim footpath. The man who had been sleeping rough on one of the benches at the foot of the church had been evicted by Friday morning, and his sleeping bag had gone with him. In the Elisabeth park there was another group of sturdy, bored police officers in unconvincing plainclothes with translucent earpieces dangling from their collars.

The whole operation to prepare Koekelberg for the visit had pacified the neighbourhood, and the junction at the foot of the basilica that morning was quiet save for the overhead whine of a police drone and the clipclopping of unseen police horses in the park.

What time was the pope due? Any minute, I said, looking first to my watch and then to the helicopter buzzing low over the motorway tunnel entrances that face the steps of the church. 9.45, I added. And it was already 9.40. “And do you know how he’s coming, by helicopter maybe?” the man asked me, both of us looking up into the malicious grey sky above us. I told him I thought probably up through the tunnels, because they had closed them city-wide for the visit. I pointed out the fleet of police motorbikes and squad cars disgorging themselves across the street but he didn’t seem convinced and kept looking up.

We were supposed to be moving house on Saturday, from a place behind the basilica to one in front of it. I had not intended to be there in front of the basilica rubbernecking with my neighbours right at the moment when the pope was expected to arrive; I was supposed to be too busy shuttling from one house to the other. But in a spare moment en route, I’d been drawn in by the slowly gathering crowd, and didn’t want to leave too soon after my short conversation for fear of appearing rude. I had not planned on engaging with the papal visit at all. I had, through the course of the preceding week, observed with lede ogen the church and city authorities incrementally close off the area around the basilica, covering over the grass lawns, blocking out onlookers with large black screens, and fencing off the green verges at the base of the church’s monumental entrance. I saw yellow road signs go up directing the various castes of liturgical guests where to go, and I saw the streets around us empty themselves of parked cars on pain of confiscation. I saw all this and the quiet trickle of massgoers climb the hill to the basilica on Saturday morning.

I am not religious, and despite my pressganged baptism into the Irish catholic church ours was an anti-clerical household. But standing there with the hum of helicopters overhead and the crowd faintly electric with anticipation, I did consider staying put next to my new friend and waiting for the pope to wheel into view in his borrowed white Fiat hatchback. A celebrity is, after all, a celebrity. And then I remembered reading earlier in the week that they’d planned to close the mass he was to do in Heizel the following day with a song composed by a paedophile priest. And then I remembered the Ryan Commission and the Murphy Report, Ferns and Fr. Brendan Smyth, the Tuam babies and the Mother and Baby Homes, the Magdalen laundries, the industrial schools, States of Fear, the missionaries and the Legionaries of Christ, the John Jay Report and Spotlight, Roger Vangheluwe, Commissie-Adriaenssens, Godvergeten and Operatie Kelk. And then I remembered he was not just a celebrity and I was not just a passive onlooker. And so I left.

Fantastic kicker.

May Sinéad O'Connor rest in peace.